|

Unit 9: Vergil Roman Empire |

|

Unit 10: Circle of Maecenas The Gods Again |

|

Unit 11: Ovid Metamorphoses |

|

Unit 12: Roland Barthes |

| Return to Front Page |

| The Roman Empire |

| According to the traditional date, Rome was founded in 753 B.C.E. by Romulus, son of Mars, on the Palatine Hill. Rome was ruled by seven kings until 510 B.C.E., when Tarquinius Superbus was driven out of the city, a republic was established, and the word rex, meaning "king", became anathema to the Romans. |

| Near of the end of the fifth century, Rome began a conquest of Italy. Over the next few centuries, the Romans waged war with the Latins, Etruscans, and other native peoples of Italy. Usually, defeated peoples became "allies" of the Romans, with loyalties strengthened by Roman support for local aristocrats, who naturally saw the oligarchic republic as an ally. Additionally, Rome established numerous colonies throughout the Italian peninsula, strategically located and connected through a network of military roads. By 270 B.C.E., Rome had finally conquered the Greek colonies in the south of Italy, including the wealthy and powerful city of Tarentum. |

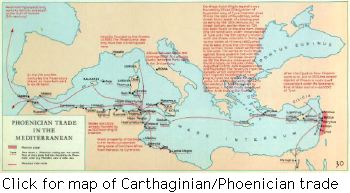

Once most of Italy was under Roman control, the Romans began military exploits beyond their borders. This brought them into rivalry with the Carthaginians, who presided over a powerful North African empire, which dominated the sea lanes of the Mediterranean and enjoyed near total control over lucrative Mediterranean trade routes. Rome and Carthage fought a series of wars, called the Punic Wars, which spanned over 100 years and were pivotal in the formation and expression of characteristics on which Romans prided themselves: tenacity, discipline, and duty. The First Punic War (264-241 B.C.E.) was fought for control of the island of Sicily, resting between the Italian peninsula and North Africa. The Romans emerged victorious despite enormous losses on both sides. Not long after, Rome annexed Corsica and Sardinia from Carthage as well. Twenty years later, in the Second Punic War, the Carthaginian general Hannibal invaded Italy with his famous march over the Alps, but was unable to win over most of Rome's allies and, despite his brilliant battlefield tactics, was eventually worn down and retreated, before being defeated at the Battle of Zama in 202 B.C.E. Rome also carried out conquests in the eastern Mediterranean, especially after the defeat of Hannibal. In the 140s B.C.E., the Romans crushed revolts in Greece and Macedonia, and liquidated Corinth in 146 B.C.E. In the same year, Rome also destroyed the city of Carthage itself, putting an end to the Third Punic War, and eradicating the final impediment to their total domination of the Mediterranean world. Once most of Italy was under Roman control, the Romans began military exploits beyond their borders. This brought them into rivalry with the Carthaginians, who presided over a powerful North African empire, which dominated the sea lanes of the Mediterranean and enjoyed near total control over lucrative Mediterranean trade routes. Rome and Carthage fought a series of wars, called the Punic Wars, which spanned over 100 years and were pivotal in the formation and expression of characteristics on which Romans prided themselves: tenacity, discipline, and duty. The First Punic War (264-241 B.C.E.) was fought for control of the island of Sicily, resting between the Italian peninsula and North Africa. The Romans emerged victorious despite enormous losses on both sides. Not long after, Rome annexed Corsica and Sardinia from Carthage as well. Twenty years later, in the Second Punic War, the Carthaginian general Hannibal invaded Italy with his famous march over the Alps, but was unable to win over most of Rome's allies and, despite his brilliant battlefield tactics, was eventually worn down and retreated, before being defeated at the Battle of Zama in 202 B.C.E. Rome also carried out conquests in the eastern Mediterranean, especially after the defeat of Hannibal. In the 140s B.C.E., the Romans crushed revolts in Greece and Macedonia, and liquidated Corinth in 146 B.C.E. In the same year, Rome also destroyed the city of Carthage itself, putting an end to the Third Punic War, and eradicating the final impediment to their total domination of the Mediterranean world.

|

| These conquests made rich Romans richer, but the poor were not seeing the benefits of expanding Roman influence. As the gap between the rich and the poor widened, several who tried to introduce reforms, such as the tribunes Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus and his brother, Gaius Sempronius Gracchus, were murdered for their efforts. In addition, Rome faced another war in Africa, a slave revolt in Sicily, and invasions of Italy by Germanic tribes. |

| Rome's troubles came to a head after the Social War (91-89 B.C.E.), when Rome's allies revolted to obtain citizenship, and there were invasions of eastern provinces by Mithridates VI of Pontus. Lucius Cornelius Sulla, consul in 88 B.C.E., was appointed by the senate to lead an army against Mithridates. However, Gaius Sulpicius, one of the tribunes, had the plebeian assembly give the command to Gaius Marius, who had held several consulships to deal with earlier Roman problems, instead. Sulla marched on Rome, drove out Marius, and murdered Sulpicius. However, when Sulla left for the east, Marius returned and seized power. But when Sulla returned, he was able to defeated his opponents (Marius had died by now) and make himself dictator in 81 B.C.E. |

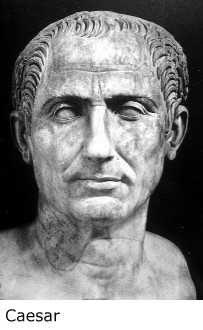

However, in the 70s B.C.E., more revolts led the generals Pompey and Crassus to power. Pompey defeated Mediterranean pirates, defeated Mithridates in the east, and reorganized the eastern provinces. When he returned to Italy, his opponents stifled his efforts to give land which he had promised to his veterans. As a result, he, Crassus, and Julius Caesar, a young and brilliant military leader, formed an alliance known as the First Triumvirate. Caesar became consul in 59 B.C.E., and later led a successful military campaign in Gaul. By the end of the 50s B.C.E., however, relations between Pompey and Caesar were strained (Crassus had died in battle in 53 B.C.E.) In 49 B.C.E., Caesar led his army across the river Rubicon (invading his own country) and defeated Pompey, and had himself declared dictator for life. Though the cherished institutions of the Roman Republic had been weakened by many decades of infighting, Caesar's crossing of the Rubicon was the final nail in the coffin. As much reviled as he was feared and admired, Caesar was murdered by a group of senators, putatively representing the institutions of the Republic, led by Brutus and Cassius on March 15, 44 B.C.E. However, in the 70s B.C.E., more revolts led the generals Pompey and Crassus to power. Pompey defeated Mediterranean pirates, defeated Mithridates in the east, and reorganized the eastern provinces. When he returned to Italy, his opponents stifled his efforts to give land which he had promised to his veterans. As a result, he, Crassus, and Julius Caesar, a young and brilliant military leader, formed an alliance known as the First Triumvirate. Caesar became consul in 59 B.C.E., and later led a successful military campaign in Gaul. By the end of the 50s B.C.E., however, relations between Pompey and Caesar were strained (Crassus had died in battle in 53 B.C.E.) In 49 B.C.E., Caesar led his army across the river Rubicon (invading his own country) and defeated Pompey, and had himself declared dictator for life. Though the cherished institutions of the Roman Republic had been weakened by many decades of infighting, Caesar's crossing of the Rubicon was the final nail in the coffin. As much reviled as he was feared and admired, Caesar was murdered by a group of senators, putatively representing the institutions of the Republic, led by Brutus and Cassius on March 15, 44 B.C.E.

|

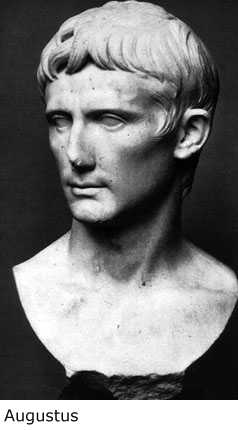

| However, the Republic was not restored. In his will, Caesar officially adopted his great-nephew, Octavian, as his son and hier. Octavian, a budding young general all of 18 years old, was told this at the same time he learned of his great-uncle's death. It was an early mark of his prodigous political talent that he was soon able to reach a power-sharing agreement with Mark Antony, Caesar's chief lieutenant who assumed he was the heir apparent, and Lepidus, another of Caesar's inner circle. These three generals divided the empire among themselves and formed the Second Triumvirate. They eventually turned on each other, Lepidus lost his influence, and Octavian finally defeated Antony at the battle of Actium in 31 B.C.E., after which Antony and Cleopatra, ruler of Egypt and lover of Antony, committed suicide. |

Once his opponents were defeated, Octavian announced in a special meeting of the Senate on January 13, 27 B.C.E. that he would restore the Republic, resigned all of his special offices, and was given the title of Augustus, "exalted," by the Senate. Given that he was part of Julius Caesar's family, he also took over that family name, and sometimes goes by "Caesar Augustus" (not to be confused with Julius Caesar). The "Republic" was thus restored, but in name only, for in addition to his title, the Senate also gave him administration of most of Rome's provinces, as well as most of its armies. Because he was also consul, Augustus was effectively the head of all the domestic government also. Any actions of the Senate against him could have been seen as treason. He sat atop what was functionally a new entity, the Roman Empire. Once his opponents were defeated, Octavian announced in a special meeting of the Senate on January 13, 27 B.C.E. that he would restore the Republic, resigned all of his special offices, and was given the title of Augustus, "exalted," by the Senate. Given that he was part of Julius Caesar's family, he also took over that family name, and sometimes goes by "Caesar Augustus" (not to be confused with Julius Caesar). The "Republic" was thus restored, but in name only, for in addition to his title, the Senate also gave him administration of most of Rome's provinces, as well as most of its armies. Because he was also consul, Augustus was effectively the head of all the domestic government also. Any actions of the Senate against him could have been seen as treason. He sat atop what was functionally a new entity, the Roman Empire.

|

| At the same time Octavian was solidifying his political control over the Roman world, he was careful to present himself and his new order as a continuation, even a restoration, of traditional Roman values. The long years of civil war had left Roman lands, cities, and sensibilities in desperate need of repair. He and his allies proceeded cautiously in political matters, eager to avoid the mistakes of their predecessors. While he acquired great power, he rejected, with much pomp and circumstance, any powers voted to him which might have suggested a monarchy or dictatorship, seeking to have himself seen as a "Princeps," a sort of "first among equals." As a part of his attentiveness to the needs of Romans for cultural stability and connection with their past, Augustus devoted time, energy, and resources to the development and expansion of Roman literature. Under the relatively lavish patronage of himself and other wealthy individuals, such as Maecenas, Roman literature flourished in the Augustan Age. These Augustan poets followed Greek examples, but, writing in Latin, also had their own ideas. Roman values and ideals were immortalized through these works. Virgil's Aeneid, an epic poem commissioned by Augustus about the founding of Rome, provided the Roman people with a sense of national identity and a common background. |

|

Sources: Hornblower, Simon and Spawforth, Antony, ed. The Oxford Classical Dictionary. 3rd ed. Oxford University Press, 1996. Van der Heyden, A.A.M. and Scullard, H.H., ed. Atlas of the Classical World. Thomas Nelson and Sons, Ltd, 1963. |

| Timeline of Relevant Events |

|

|

|

Copyright 2000-2020 Peter T. Struck. No portion of this site may be copied or reproduced, electronically or otherwise, without the expressed, written consent of the author. |